Institute for Liberal Arts News

News Archives

-

November 7, 2025

Building Global Leadership through Hands-on Practice and Intercultural Exchange

-

October 25, 2024

International students enjoy tea ceremony event

-

October 18, 2023

Japanese Section hosts mock Japanese Language Proficiency Test for international students in academic year 2023

-

September 13, 2023

International students complete Intensive Japanese Course with poster presentations

-

August 24, 2023

First in-person Star Festival event in four years at Japanese Section

-

June 21, 2023

International students enjoy Manga and Illustration Festival

-

March 22, 2023

International students give final presentations to youngsters upon completion of Japanese courses

-

February 24, 2023

International students in Intensive Japanese Course tour Kamakura

-

October 18, 2022

Fifteen international students complete Intensive Japanese Course

-

June 2, 2022

New international students of spring 2022 join Welcome Coffee Hours

-

May 25, 2022

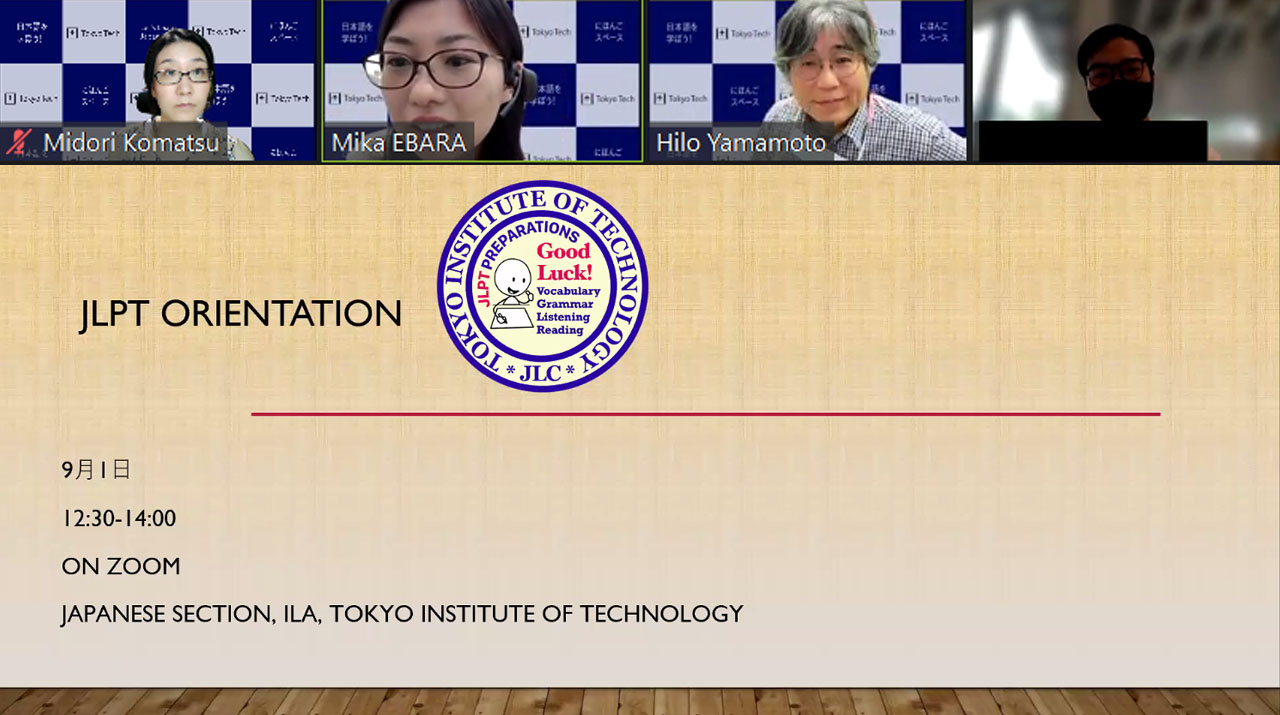

International students learn about JLPT in Japanese Section info session

-

May 20, 2022

Online Hinamatsuri 2022 immerses students in culture and language

-

March 11, 2022

The Audibility of Strangers: Music and Disparate Japanese Communities in Prewar "White Australia."

-

February 25, 2022

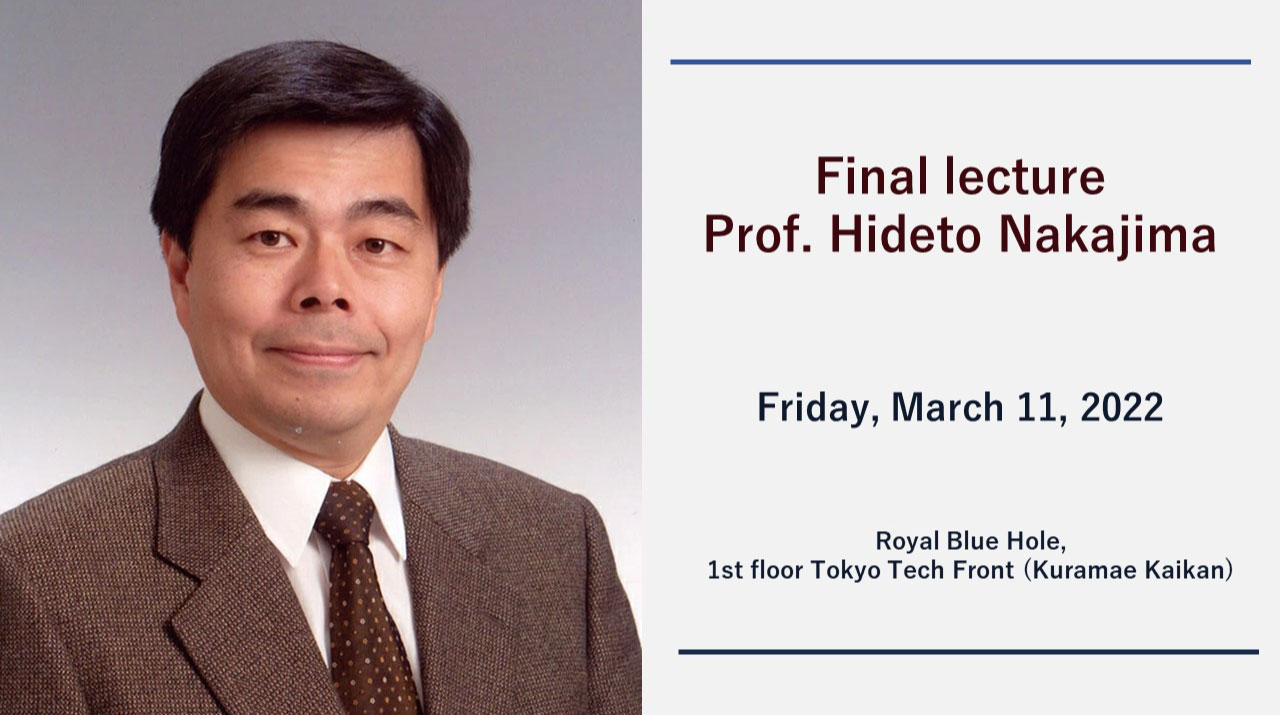

Final lecture of Prof. Hideto Nakajima

-

February 21, 2022

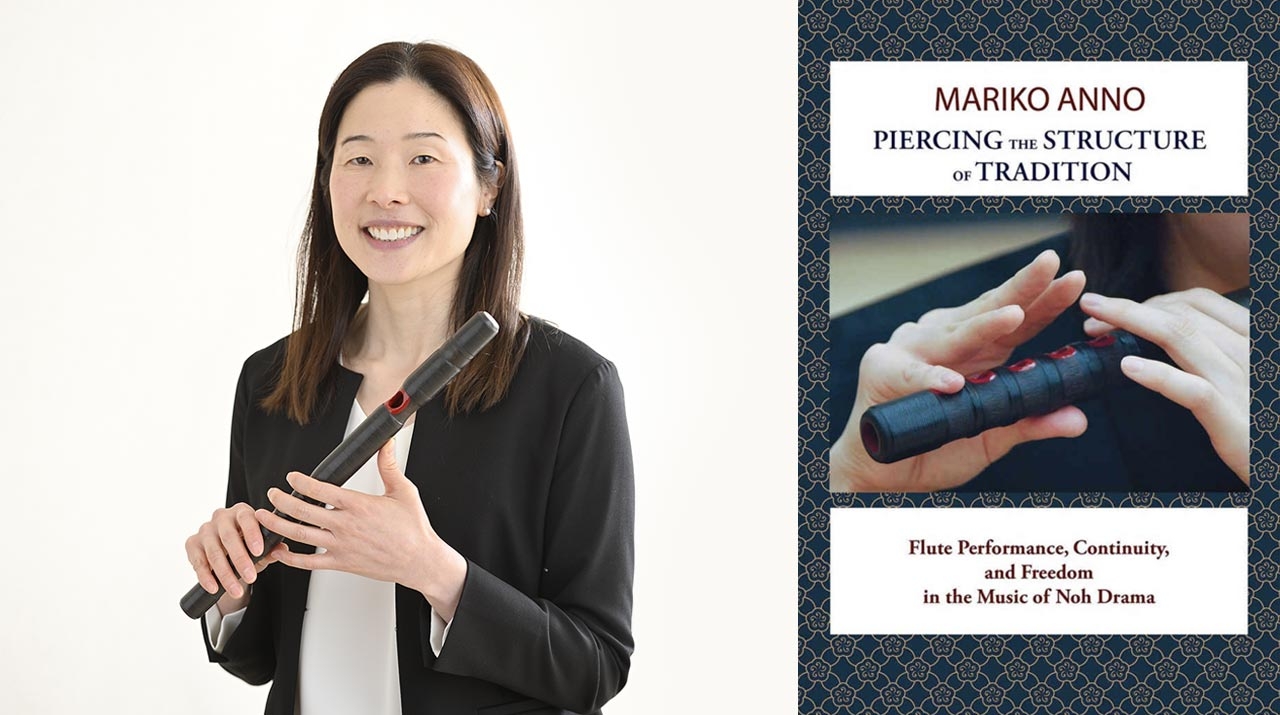

Report on Tokyo Tech ANNEX Berkeley Colloquium: Piercing the Structure of Tradition

-

January 19, 2022

New Year's card workshop offers students much-needed social activity

-

January 17, 2022

Movie Seminar restarts after two-year break

-

December 24, 2021

Professor Yamamoto and his colleagues received the Digital Humanities Historical Institute Poster Award from the University of Tokyo

-

November 11, 2021

Welcome Coffee Hours brings together new international students of fall 2021

-

October 29, 2021

JLPT orientation held for international students

-

October 29, 2021

Welcome Coffee Hours held online for new international students

-

October 4, 2021

Online Open Space connects language students even during spring break

-

September 16, 2021

Lunchtime English Café launches online

-

April 30, 2021

Welcome to the World of Liberal Arts, a Taste of Life

-

April 30, 2021

Using ‘Theater’ Performance for Communication in Classes and Local Events

-

April 30, 2021

Dual-Lens Meta-Analysis of Science: Scientometrics, and Science and Technology Studies

-

April 30, 2021

More Questions than Answers—The First Step in Liberal Arts Education

-

April 30, 2021

Intimate Relationship between Sports and Science Enhances Competitiveness of Paralympians

-

April 30, 2021

Rediscovery of Deep Links Between Japan and China: Inspiration to Cultivate Broad, Multi-faceted Perspectives

-

April 30, 2021

Shakespearean Films, Academic Writing Education, and English Learning Using Movies: Three Ingredients to Enrich My Research

-

April 20, 2021

Students connect through online Hinamatsuri doll festival

-

April 19, 2021

Religious Studies Deliberate Values. Being Conscious of Values Can Liberate Us

-

April 19, 2021

Learning about Muscle and the Importance of Exercise Makes a Difference in Life

-

April 19, 2021

Provoking Students to Elicit Their Direction of Inquiry

-

April 19, 2021

Creating a Learning Environment about Leadership

-

April 19, 2021

Learning the Values of Coincidence Through Art and Becoming Free from Your Need to Control

-

April 19, 2021

Sharing a Fascination for Novels with Students

-

April 19, 2021

Why Tokyo Tech Students Need Liberal Arts Now—as Recommended by Akira Ikegami

-

December 12, 2019

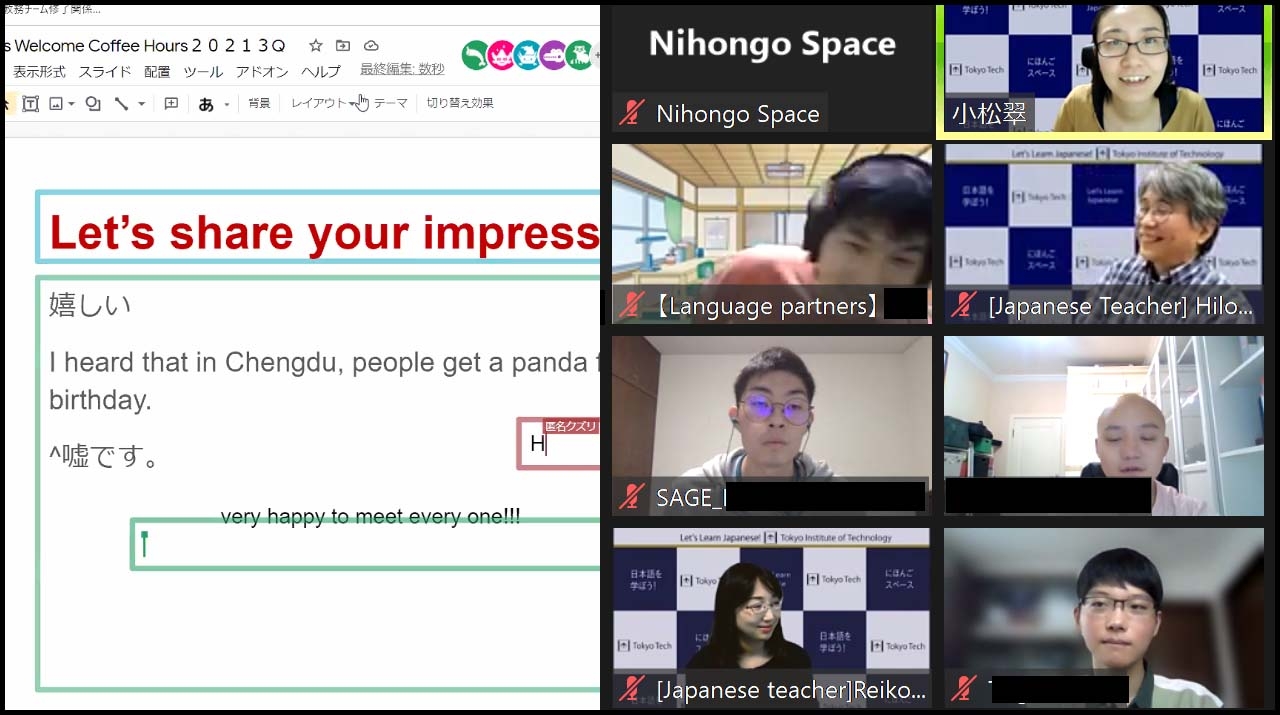

Nihongo Space offers international students Japanese language support

-

August 29, 2019

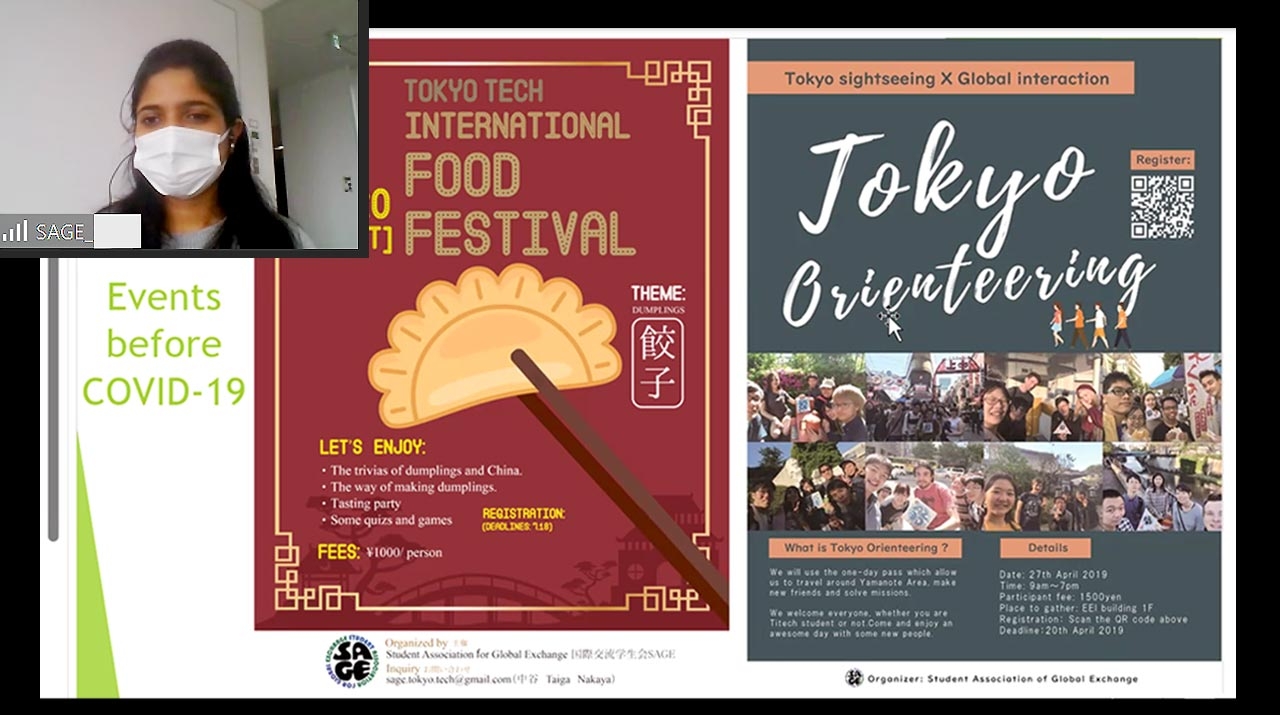

International students enjoy Welcome Coffee Hours and Japan-themed events

-

July 11, 2019

Tokyo Tech student in finals of 60th International Speech Contest in Japanese

-

January 7, 2019

Liberal Arts Final Report illuminates students’ individual paths

-

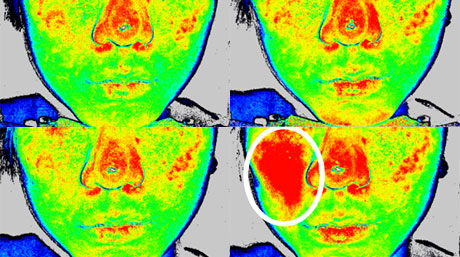

November 21, 2018

Ready for a close-up: The science behind face massage rollers

-

November 16, 2018

Unique student initiatives born from Tokyo Tech Visionary Project

-

November 12, 2018

Multisport Camp for elementary school students

-

November 7, 2018

RENGO trade union leaders provide sociology lectures

-

November 1, 2018

Tokyo Tech's newest Graduate Student Assistants certified

-

July 31, 2018

Report: Special Lecture of Tokyo Tech Liberal Arts Courses 1Q 2018, "Succession of Technology and Culture"

-

May 31, 2018

The 1st Imperial-Tokyo Tech Global Fellows Programme 2018

-

May 17, 2018

"Take a soldier, take a king" — Tokyo Tech does Shakespeare's Henry V

-

April 12, 2018

Ten years of friendship and exchange with Kakuda City

-

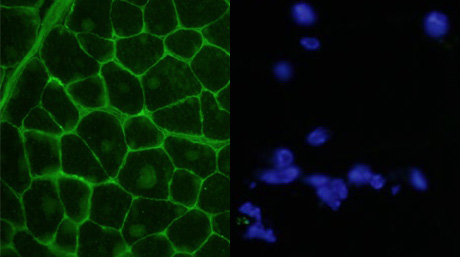

January 26, 2018

0.6% soy isoflavone in the diet decrease muscle atrophy

-

December 28, 2017

The research of Classical Poetic Vocabulary won the best poster award of the conference of Computer and Humanities 2017

-

October 31, 2017

New international students welcomed during Welcome Coffee Hours

-

February 7, 2017

Godiva Managing Director Chouchan speaks on business and the way of the bow

-

July 20, 2016

Professor Alvin E. Roth interviewed in Contemporary Society class

-

April 20, 2016

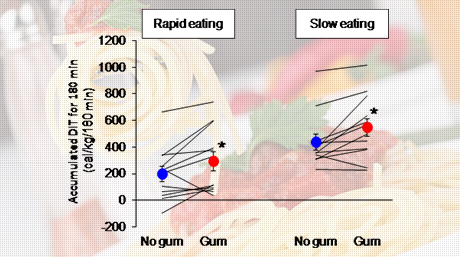

Something to chew on: how low-energy gum may help with your waistline