Institute for Liberal Arts News

Welcome to the World of Liberal Arts, a Taste of Life

Professor Taro Yamazaki, German Literature, German Opera

Language is culture, resonance

Fellow Tokyo Tech students, “Raise your voices!”

I have taught German language classes at Tokyo Tech since 1993.

For a long time, students studying science have frequently selected German for their second foreign language requirement. That number has dropped in recent years, but somewhat more than one-third continue to select German.

Our introductory class begins with daily greetings in German, while students headed toward studying aboard in German-speaking countries join the intermediate and advanced classes. In all of my instruction, I explain that language is culture.

Language reflects the world of the speaker. For instance, the predicate consisting of verbs and auxiliary verbs in German grammar often comes at the end of the sentence, rather than immediately after the subject. As an additional key feature, this frame structure also allows the insertion of various additional words in between. In my mind, this construction reveals the spatial sense of ancient Germans who lived deep in the woods and made efforts to see across considerable distances.

The English language uses the expletive pronoun in expressions about the weather or time, like “It is raining” or “It is ten o’clock.” The definitive meaning for “it” in these cases seems to refer to divine providence or heavenly proclamation as assumed by ancient people, or nature beyond human control. Interestingly, the same English “it” in German is “es,” which, as the subject, frequently begins sentences that describe physiological or psychological conditions like being hungry or feeling fearful. This reference suggests an “inner nature” in the human body or mind beyond our control. Since Freud, “es” became established to mean the subconscious and thus also used an ordinary noun.

Audiovisual materials help to bring culture and history of German-speaking countries closer. When the word Burg (castle) appears, I explain how Bürger (citizen) originally meant the people living within the castle walls. Seeing the structure of a medieval city surround by castle walls, students discover that arterial loops of today’s cities run where the castle walls were dismantled in the 19th century. I follow with an explanation about why most railway terminals of large cities are not in the city center, but usually a short distance away.

Pronunciation, incidentally, is also important. Tokyo Tech students generally speak softly. During class, I approach the direction of a voice, peer into a face, and finally identify the speaker. Muttering face downward is completely inaudible. I ask for facing straight and speaking in a loud voice.

In line with this desire, I also provide time for everyone to read famous poems out loud during class. So they realize that “Words, above all else, are sound,” I play CDs of Schubert songs based on the poems, or sometimes sing them myself. I sing as a side activity and perform in an amateur musical group. This pastime becomes useful in my occupation as a teacher (laughs).

The second foreign language was a first-year undergraduate class up through 2016. Most recently, the subject is required for second-year undergraduates. I worried that the fresh enthusiasm at the time of entering university would no longer be seen, but my fears were unfounded.

The Tokyo Tech Visionary Project launched in 2016 seems to be making a favorable impact. Student engagement in the classroom has become visibly more active.

All first-year undergraduate students entering Tokyo Tech immediately enroll in Visionary Project. Scholars, journalists, NPO leaders, and clergy at the frontline of our society present in the lecture hall. These presentations constitute the input for consequent group work in classroom sections of 30 or fewer students. Everyone collects impressions and analyzes the content presented by the speakers. In the classroom, we split further into groups of four to discuss and bounce each other’s thoughts around. Obviously, most students have hardly met before, so shyness abounds initially. As the conversation unfolds, the group work warms up. New ideas come forth through dialogue that would never enter one’s own mind alone, and the enjoyment of active learning can be felt strongly. This was never observed before Visionary Project.

Universal themes capture society and people

Comprehensive fine-art opera analyzed deeply, tightly, for ease of understanding

Along with German language and Visionary Project at Tokyo Tech, I teach Introduction to Opera as a humanities and social science lecture. The survey of song, orchestra, language, and performance are integrated in this fine art. The multiple facets of opera are explored.

Not merely entertainment, opera is a fine art that has evolved to educate citizens. In Europe, the theater is staunchly considered a public educational institution for citizens to independently contemplate politics, for example. All cities with population of 100,000 or more have a theater in Germany. Once a week, citizens historically gather in the evening at the theater to watch a work of fine arts, followed by political debate.

The themes portrayed in opera are universal and not necessarily ancient. Composer Toshio Hosokawa’s Stilles Meer is a new opera work set in Fukushima after the East Japan Earthquake. Oriza Hirata produced the opera for its premiere in Hamburg, Germany.

My instruction examines contemporary works like this to show how problems in society are weaved into an opera production. Although the course is called Introduction to Opera, my teaching gets into fairly specialized details, like the historical backdrop of enlightenment philosophy reflected in Mozart’s works and musical perspectives, such as what certain orchestral melodies mean.

The operas covered in the lectures are relatively major works and timely selected according to upcoming performances. For students who gain an appreciation for opera in the classroom, I definitely encourage going to live performances in the theater.

Wagner’s turbulent life

My personal cumulative research concerns Richard Wagner’s operas. The approach is varied, analyzing lyrical commentary, performance history, and productions.

For the portions that the superficial dramatic pace cannot fully express, Wagner augments the storytelling through sound and stage directions. For example, in The Ring of Nibelung the protagonist is led to drink an amnesia potion, betrays his wife, and later is led to drink a potion that restores his memory.

The stage direction “His gaze fell while in reflection …” during the scene of drinking the potion that restores the memory is identical to the scene of drinking the amnesia potion. A deep reading suggests this action prompts the protagonist’s consciousness to return to the moment of losing his memory or even before that. The amnesia potion itself is a tool of fantasy within a mythical setting, but Wagner has completely illustrated deep human subconsciousness through sound and words before the concept of subconsciousness prevailed. He pre-empted Freud and Jung in this sense.

In addition to psychology, Wagner’s works tie into insights across various academic disciplines, including philosophy, history, sociology, and cultural anthropology. The dramas speak of the origins and conclusions of civilized society and symbolically criticize modern scientific civilization and monetary economy. The depth and breadth of his works are unimaginably immense.

I am also interested in Wagner as a person. He not only wrote the scripts, but authored treatises on society and the fine arts, participated in a revolution, built a theater dedicated to his works, and founded a music festival. The life of Wagner exceeded the framework of being a musician.

Recently, I have taken particular interest in the numerous letters he wrote. Although the letters have not been the subject of much research, his emotional ebb and flow and true sentiment can be learned. He wrote to his fellow revolutionaries sentenced to death, “I am personally happy now. Do not worry, as I will live on your behalves.” At about the same time, he promises to elope with a young married woman, yet for lack of money expects assistance from the household of his unfaithful partner.

Moreover, a lengthy farewell letter to his wife, 10,000 characters when translated into Japanese, makes no mention of his elopement at all. He writes that they should live apart, because their personalities do not match, but best not to get divorced … . He has so many places to be denounced (laughs). The study of the 19th century in which Wagner lived becomes an interesting exercise through his words and actions.

In order to deeply appreciate life, and

when life trips you over

What are the liberal arts? Not immediately useful, but clearly nutrients for the soul. The term “liberal arts” originally refers to the proficiency to liberate the human mind, but I wish to add an additional definition: Wisdom to enrich human life.

Today, we are awash in information, and society considers efficiency as paramount. Principles of efficiency, however, ultimately and necessarily omit certain elements that we need to relish. In a nutshell, liberal arts teach us to appreciate what we might otherwise neglect.

Why do humans live their lives? The answer, biologically as a species, is to leave one’s own DNA for the future. If each of us were to consider the alternative meaning of life, the conclusive answer appears to be a deep appreciation for human things.

A certain amount of time is necessary to appreciate something. For instance, if the purpose of a meal was merely energy intake, the era to accomplish that with a single pill is sure to arrive soon. But nobody would accept that willingly, because the joy of eating colors and establishes the lives of humans. The summary of a novel or opera as information is hardly an appreciation of the entire work.

On another note, when life trips you over, liberal arts can be supportive. The appreciation gained from music and reading provides nutrients for the heart and can give you the hope to live. Such times may lie ahead of you.

![]()

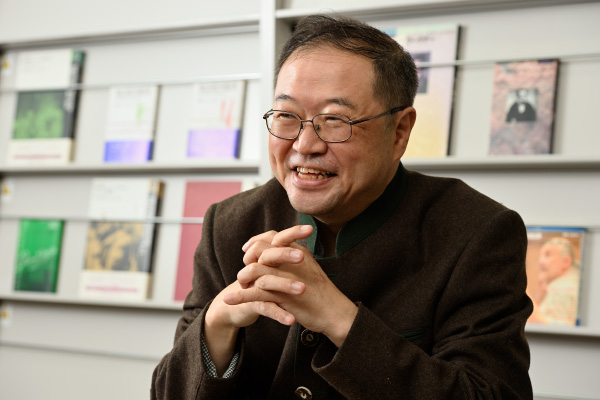

Professor Taro Yamazaki

Research Fields: German literature, German opera

Born in 1961. Graduated with degree in German Language and Literature, School of Letters, The University of Tokyo, and held post of Assistant Professor. Joined Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1993. Principle works include 《ニーベルングの指環》教養講座 読む・聴く・観る! リング・ワールドへの扉 1 (Liberal arts course for reading, listening to and watching The Ring of Nibelung: gateway to ring world) published by Artes Publishing, translation of The Wagner Compendium (supervisory editor and co-translator, Heibonsha). Serves on the board of Richard-Wagner-Gesellschaft Japan. Previously joined opera performance productions as dramaturg for The Abduction from the Seraglio and The Magic Flute by Mozart (Nissei Theater, 2004 & 2008) and The Cunning Little Vixen by Janacek (Nissei Theater, 2006).

Related Works

-

《ニーベルングの指環》教養講座 読む・聴く・観る! リング・ワールドへの扉1

(Liberal arts course for reading, listening to and watching The Ring of Nibelung: gateway to ring world)

-

(The Wagner Compendium)

-

(Opera producer Peter Konwitschny)

1 Published in Japanese