Institute for Liberal Arts News

More Questions than Answers—The First Step in Liberal Arts Education

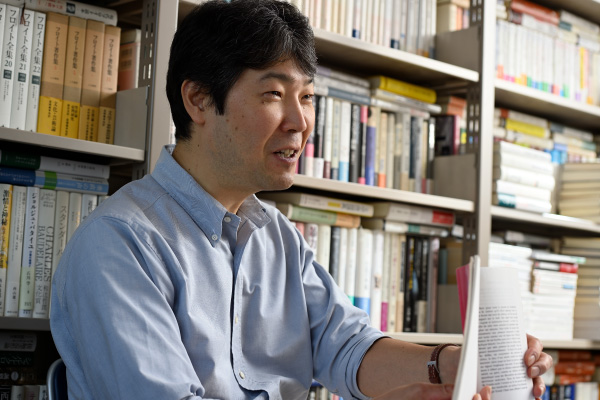

Professor Koichiro Mitsubori, French Literature

Learning French brings you into contact with the culture and perspective behind it

I teach French, and my coverage includes beginner to advanced levels.

Learning a second foreign language is mandatory at Tokyo Tech, but a language other than English, such as French, is not usually required for scientific research. For this reason, my class concentrates on learning French culture, ideas, and ways of thinking, rather than solely acquiring practical language skills. What matters is the experience of studying a new language because it may help them in the future (e.g., when a student might live in other countries). In this sense, I believe including second foreign language courses in the university curriculum is significant, providing an opportunity to learn what it takes to master new languages.

Let’s explore how you learn the language in my classes. For pure beginners, there are basic pronunciation and grammar sessions, but I try to include as many oral exercises as possible so that they can actively enjoy learning French. More advanced learners who are interested in practical language skills will go through more intensive training. We also use various materials taken from the Internet, newspaper, novels, and TV news so that they can be exposed to information in French. In some classes, there are sessions to promote mutual support among learners, where those who have lived in the French communities will share their experiences and insights on cultural differences.

My French lessons aren’t limited to regular courses. For example, some students may think of switching to soft science, but they only completed the elementary course of French, which is required as a second foreign language to enroll in a graduate school. This is where my dedication can fit in; I provide them with concentrated one-on-one training, which I value as much as the regular classes.

Why a young literature boy and wannabe poet turned to be a French literature researcher

My specialized field is French literature. But it was not my original pursuit. As a literature-loving teenager and adorer of poets like Chuya Nakahara and Mitsuharu Kaneko, I planned to study modern Japanese literature at university. On the other hand, my interest in French was also growing, since French literature had influenced all my favorite Japanese writers, and Modern French Philosophy had caused the boom of the new academism movement back then. Therefore, I chose French as my second foreign language without any hesitation. It was probably an illusion for a young man, but mastering French seemed like the door to the intellectual universe. I was thinking of becoming a writer of literature reviews.

Gradually, a harsh reality began to reveal itself. The number of wannabe writers at Waseda University’s Faculty of Letters, where I enrolled, was like that of stars in the sky, and many talents were twinkling. Considering my odds, I started to shift my focus to mastering French when I was a 1st-year student. Becoming an outstanding writer was difficult, but living as a top businessperson was almost unimaginable for me. Therefore, I began searching for my path as a French literature specialist. Still a hazy dream then, but it developed into a solid decision when I lived in Dijon, France, to study before graduation. During my one-year stay there, I significantly improved my French, and even more importantly, my compatibility with the local culture and customs turned out to be excellent. All this eventually led me to stay in Paris later for a total of seven years during my master’s and doctoral courses.

My master’s and doctoral dissertations featured an author named Julien Gracq (1910-2007). Almost unknown in Japan, he is one of the leading writers of 20th century French literature. I encountered his books through a French teacher I met in Brest (a city in Brittany), where I was preparing my French for my first study abroad program in France.

The book introduced by the teacher enthralled me first with its appearance. It was an old-fashioned, so-called “French binding style” book comprising letterpress-printed pages with edges uncut. Secondly, I became enchanted by its content featuring dignity, nobleness, and density. For his highly refined writing, Gracq was selected for the Goncourt Award, the most prestigious literary award in France in 1951, which he refused due to his reluctance to “ride the trend.” His nobleness, unaffected by vulgarity, trying to pursue his universe deeply resonated inside me. At the same time, the fact that Taijiro Amazawa and Motoo Ando, my favorite poets, had translated his works fueled my fascination with Gracq.

Even now, long since my doctoral dissertation, I remain his admirer. Having engaged in other activities, publishing papers on other writers, and translating modern French literature, I believe it’s time to return to his works. Besides that, as my second topic, I’m thinking of studying how World War II is related to French post-war literature. That would probably be my lifework and deserves my dedication because it would give us hints to address the post-war Japanese society and is closely related to the future of modern Japan.

Dedication to liberal arts education

gave shape to the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project

It was in 2010 when I joined Tokyo Tech, first at the Foreign Languages Research and Teaching Center, and then at the Institute for Liberal Arts (2016) as one of its founding members. My involvement in founding the Institute began in 2014 when I heard a rumor that secondary foreign language courses might be removed from the mandatory curriculum. This seemed a devastating decision to me, and I thought that taking such an action was the equivalent of discarding the university’s top-class status. I immediately went to management and requested the retention of secondary foreign language courses as a mandatory part of the curriculum, and they agreed. However, in exchange, they ordered me to develop new projects alongside other liberal arts teachers and I joined the working group led by Professor Noriyuki Ueda.

Luckily enough, using workgroups in classes had been my regular practice when I was teaching at Waseda University, and I soon became a passionate member of the new liberal arts curriculum team. As a result, with the support of the other teachers, I was able to develop the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project. The late Professor Masanori Kaji, who was teaching the history of science and was the originator of said project, always endorsed the importance of secondary foreign language courses when necessary during the process. I’m very grateful to him, not only in that sense but also for his valuing of my skills in developing detailed schemes and scenarios for the project. Thus, the basic framework of the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project was born, comprised of lectures by famous guest-speakers combined with small-group sessions.

Talking about the lectures by celebrities in the project, we incorporated a unique aspect. That was to include the motivation that brought each speaker to their current research or job in their lectures. It’s based on the idea that the area of liberal arts one has mastered cannot be separated from that person’s personality and life. For example, if a lecturer in sociology shares a life-story about how they became involved in Minamata disease, that would make students see that liberal arts are beyond knowledge and deeply rooted in the being of each individual.

Liberal arts are the accumulation of unanswered questions that lead to deeper learning

My definition of liberal arts education is “to embrace extensive and deep concepts that you don’t understand.” In other words, the number of unanswered questions one can hold determines the degree of one’s liberal arts capacity, not the quantity of knowledge or number of correct answers they have. That capacity becomes enhanced even more when one encounters unanswered problems. In that sense, I think the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project is a disciplinary platform to discover questions or identify issues, rather than seek answers. That’s why I always encourage students to voice whatever question they may have, however stupid it may sound.

Let’s talk about another outstanding aspect of the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project. Everyone has unique views, and when it comes to the Institute for Liberal Arts, the diversity is almost uncontrollable. Therefore, while maintaining the relevance and integrity of the whole curriculum, individual exercise courses are all up to their teachers, reflecting personal ideas and methods. Mutual trust between the project management team and other teachers is entirely appropriate since all members at the institute are firmly committed to delivering their best.

Then, how has the project benefitted students after three years since the start? Even though the effect seems moderate, I have a clear impression that their reports have improved, and their participation in the class has become more active and engaged. But those changes are still superficial, and we will need more time to harvest more substantial fruit from our liberal arts education.

However, I believe the project shouldn’t necessarily change students. Many Tokyo Tech students call themselves “a nerd” or “a mild sociopath case,” but how they define themselves doesn’t matter. They can remain as they are and look at the positive side of such personality. For example, I would call myself a literature nerd with a mild touch of pessimism. But thanks to those propensities, I can appreciate old literature works and enjoy the aloneness of absorbing in research.

Exploring the depth of solitude can sometimes cultivate “circuits” to sociological breakthroughs. In that context, I think that the value of using solitude to face something deeply could be integrated into university education more explicitly. How to communicate this idea is my question, whose answer I haven’t found yet.

In conclusion, I want to emphasize again that “you don’t know” is the first step of liberal arts learning. I’m ready to deepen many don’t-knows together with you, fellow students, at the Institute for Liberal Arts!

![]()

Professor Koichiro Mitsubori

Research Field: French Literature

Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1972. Graduated from the French Literature course, Faculty of Letters, Waseda University. Enrolled in a doctoral course at the University of Paris VIII. Started to serve as an assistant researcher at the Faculty of Letters, Waseda University in 2006, and as an assistant professor at the same faculty. Joined the Foreign Languages Research and Teaching Center, Tokyo Institute of Technology as an associate professor in 2010. The current position since 2021. Specializes in French literature and comparative literature. Translated works include 二十世紀フランス小説 1 ( Le roman français depuis 1900 ) (Twentieth century French novels) by Dominique Rabaté, published by Hakusuisha, ルイユから遠くはなれて 1 ( Loin de Rueil ) ( The Skin of Dreams ) by Raymond Queneau, 本当の小説 回想録 1 ( Un vrai roman, Mémoires ) (A real novel, memoirs) by Philippe Sollers, both published by Suiseisha. Co-authors 引用の文学史──フランス中世から二〇世紀文学におけるリライトの歴史 1 (History of literary citations: History of rewriting in French literature from the Middle Ages to the 20th century) published by Suiseisha and others.

Related Works

-

Le roman français depuis 1900

(Twentieth century French novels) -

Un vrai roman, mémoires

(A real novel, memoirs) -

Loin de Rueil

( The Skin of Dreams )

1 Published in Japanese

Updated August 11, 2021