Institute for Liberal Arts News

Using ‘Theater’ Performance for Communication in Classes and Local Events

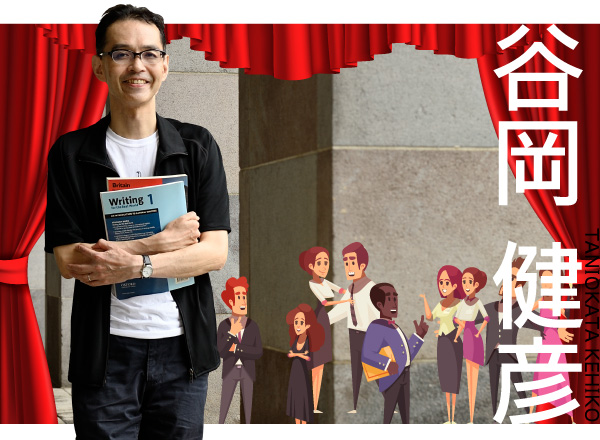

Professor Takehiko Tanioka, Contemporary British Theatre

Theater workshop techniques can promote dialog and sharing among students

As a teacher of English at the Institute for Liberal Arts, I focus on fostering students’ global viewpoints through materials related to international issues and foreign cultures. Since learning languages can polish one’s communication ability, my role is to convert the classroom into an ‘environment’ where students feel welcomed to voice their ideas freely.

To that end, I often break the ice by throwing questions or give a hearty laugh to anything they say intended for amusement. Then, they get the message that I’m not a scary teacher, and some elements of fun are allowed in my classroom. Creating a relaxed atmosphere is very important, particularly if many Tokyo Tech students are so-called ‘straight-A’ students, who may be afraid of saying inappropriate things that may sound stupid. Such pressure must be removed, and I think that’s crucial to start my class.

How to engage students actively in my English class has been my primary concern, especially since the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project, a required liberal arts course for 1st-year undergraduate students, started in 2016.

I often use theater workshop techniques as a way to involve students in the project activity described above. Here is an example of how it works: In a communication practice session, I might give them the theme “Words I Couldn’t Say at That Time” and ask them to write down what they had to say. All of their written situations are then shared among individual groups of four. Suppose that, among those unspoken words, there is a sentence such as, “Could you spare me some pencil leads?” Then, I ask the owner of the phrase to describe the situation. He might explain that it occurred in the middle of a test, and that, if he had asked this question of his neighbor, he might have looked like he was cheating. Once the details have become clear, the next assignment is to recreate the scenario in a drama.

But the rule here is that the owner of the words – say, Mr. A – cannot be the protagonist himself, and he must give the role to someone else – Mr. B, for instance. To complete the drama, Mr. A must exploit his communication skills to detail the incident for Mr. B, the performer, who requires the ability to listen intently in order to achieve understanding. Through this process, the former can observe his behavior objectively while the entire class can develop their mutual fellowship by sharing his experience.

Motivated by the enthusiasm of other teachers devoted to liberal arts education

My research field spans contemporary British theatre, and my current practice includes the translation and review of plays. I even performed in dramas back in university days. As my duty at Tokyo Tech was teaching English, my research and teaching had rarely crossed each other until the establishment of the Institute for Liberal Arts. Since then, everything has changed. With the restructuring of liberal art curriculums, which included active-learning activities such as the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project and Liberal Arts Final Report, I came to be even more convinced that my theater experience can make a difference in education.

Talking about my management role at the Institute for Liberal Arts, I take charge of planning and public relation activities as one of the four associate deans. When I joined the project “Tokyo Tech Education Reform” in 2016, my first honest impression was that it might end as another case of merely switching one organization name to another. But as my involvement in the project as a language teacher deepened via intensive discussions with other teachers, I gradually learned the genuineness of their pursuit of change.

They meant real changes. For example, the late Professor Masanori Kaji invented the Visionary Project, oriented for the 1st-year undergraduate students, featuring two-fold classes with lecture-halls and small workgroup sessions combined. His passion for education was so intense, and other teachers, including Professor Noriyuki Ueda, the current dean of the liberal arts institute, were ready to dedicate whatever they had for the sake of students. That was indeed a strong push, urging me to do something I could do.

There was another key figure, Professor Tamio Nakano, the initiator of workshop-style class at Tokyo Tech. My very idea of using theater techniques in teaching surfaced in my mind when I attended his class for the first time.

Contemplating that inspiration made me realize that physical movements or performing roles could settle learning more viscerally into their beings than seated discussions. Thus, I shared my theater skills and techniques with other project members. That’s not all. My theater event and audience seat management skills achieved on my university days now contribute to planning and operating events hosted by the Institute for Liberal Arts.

After a series of trials and errors, we, including Professors Koichiro Mitsubori, Tatsuya Yumiyama, and Tamio Nakano, received the Best Teacher Award for the “Design and Operation of the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project” in 2016. That was indeed a great joy.

Bonds with students and the local communities

ever strengthened through theater activities

The Institute for Liberal Arts also dedicates itself to local community-oriented activities. One of them is the “Voice Shakespeare Works” series, which started in 2017. Each season comprising five sessions features one of his plays, such as “Macbeth” and “Tempest,” which are explained, studied, voice-read through workshop activities, and eventually performed at recitals. Originally devised as a hopeful avenue of communication between Tokyo Tech students and community people who are often older than them, the event has now become an opportunity for exchange that is cherished by the locals.

An outstanding example is the workshop “Ookayama Stories,” which spawned a group called “Theater Ookayama.” The Ookayama Stories workshop encourages each member to bring their episodes related to the place of Ookayama, share them, and play them in monologues or group performances. Both students and local citizens value this activity as an opportunity to share the individual stories of the town.

We also hosted a symposium called “Katsu Kaishu and New Era,” jointly with the Ookayama Town Development Council, the other day. The event was to commemorate the opening of the “Katsu Kaishu Memorial Museum,” built beside Senzoku Pond, to honor this political leader at the dawn of the modern age in Japan. During the duration of this event, the said Theater Ookayama performed their short play related to this historical figure. The event was a great success, attracting as many as 280 visitors, mainly comprising the locals.

Another hit was a symposium held to celebrate the 100th birthday of Yuzo Kawashima, a famous film director, planned by Tokyo Tech Associate Professor Kyohhei Kitamura. Inviting Koji Fukada, a contemporary renowned film director, further boosted the celebration, which was already exciting with the charming teachers at our institute on stage! I’m thrilled to see how our events unique to Tokyo Tech entertain and satisfy people because I believe it’s essential for a university to be able to be part of the local fabric through exchange activities.

Every experience cultivating you and new encounter possibly changes you

Outside my specialized fields, I’m also a devoted haiku poet. It all started when I began frequenting a pub called “Ginkantei,” a hub for haiku poets. Soon, I was invited to a haiku club by Master Inao Ito, the owner of the pub and the club, as well as other regular pub customers. It’s almost a decade-long activity, and I even host a haiku club at Tokyo Tech. Strangely, composing haikus seems to be highly compatible with science students. It’s probably because of the process of trying to put bits of imagination into the required format, just like fitting puzzle pieces into the entire picture. There are many celebrities in the science and medical fields who enjoy creating haiku. That might be, in a way, an example of how they can enjoy their art activities using rich experience in their areas.

So what are liberal arts in a nutshell? I think they are the accumulation of how we have lived and what we have experienced. Here’s an interesting remark by a teacher in a Liberal Arts Final Report review meeting: “We can teach students dissertation skills, but when it comes to the content, it only represents their efforts in three years.” It means that merely reading several books doesn’t make an excellent report unless it’s based on students’ unique experiences, which eventually would make a difference.

Liberal arts are necessary for us, but they are less practical and urgent, compared with civil engineering and engineering. But how hard and dry our life (or student life) would be without them? If competitiveness drives the science, technology, and business fields, I think it’s the principle of “co-creation” that guides the Institute for Liberal Arts. It uses competition not to decide winners and losers but mutually enhance the other party’s expertise. All this is possible at Tokyo Tech, and I believe it’s incredibly significant.

Tokyo Tech is a university that attracts highly brilliant students from the world, holding outstanding teachers, ready to offer an impressive array of the most sophisticated knowledge and experiences. In that sense, an unexpected turn can happen in your life after discovering your hidden potential. A new path, unimaginable before the enrollment, can open up in front of you.

For example, I know someone, a member of my Tokyo Tech Haiku club and former student of physics, who switched his major from the School of Science to the School of Life Science and Technology, after awakening to the charm and mystery of Japanese sake. He has even asked for a leave of absence to undergo the initiation to become a Toji or Sake Master. Such a thrilling career shift can remind us of the uniqueness of Tokyo Tech, where an advanced level of positive competition is available in all fields. You are young, and your learning has just begun. You don’t need to walk on an already-laid rail. Use your life as a student to meet people, experience the world, and discover your true path.

![]()

Professor Takehiko Tanioka

Field: Contemporary British Theatre

Born in Osaka in 1965. Specializes in contemporary British theater. Completed the doctoral course at the University of Tokyo. Has served as a faculty member of the Center for Foreign Language Studies and Education at the Tokyo Institute of Technology since 2005. Current position since 2016. Authored 現代イギリス演劇断章 1 (Notes on contemporary British drama) published by Chamomile and co-authored スコットランドの歴史と文化 1 (Scotland’s history and culture) published by Akashi Shoten. Translated books include Colin Joyce’s 「ニッポン社会」入門 1 (How to Japan A Tokyo Correspondent’s Take) published by NHK. Also translated many contemporary British plays such as Sarah Kane’s 4時48分 サイコシス (4.48 Psychosis) (included in the No. 8 issue of Butai Geijutsu) and David Greg’s あの出来事 (That Incident) (performed at the New National Theater in 2019). Joined the Ginkan Haiku Club in 2011 when it was established and was promoted to a regular member in 2012. A member of Haijin Kyokai or the Association of Haiku Poets.

Related Work

-

(Notes on contemporary British drama―36 smart lines heard on the stage)

1 Published in Japanese