Institute for Liberal Arts News

Religious Studies Deliberate Values. Being Conscious of Values Can Liberate Us

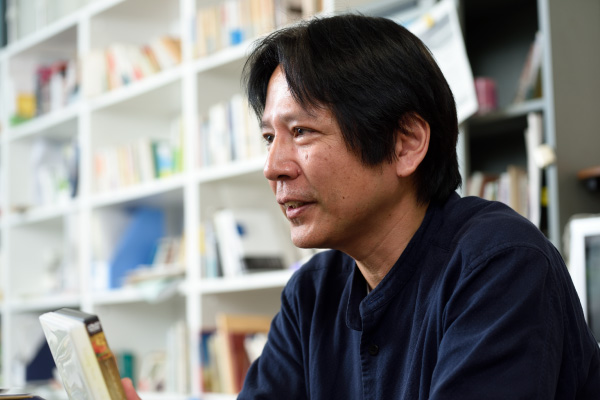

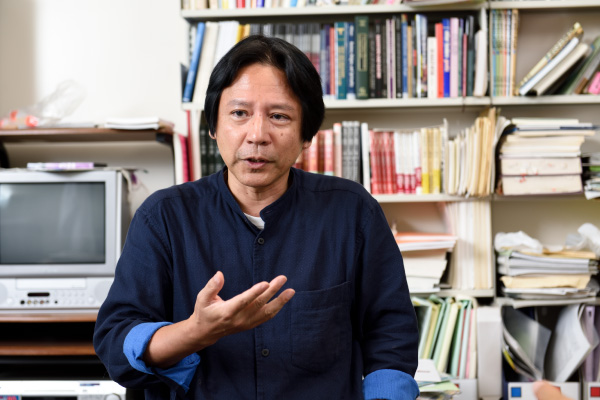

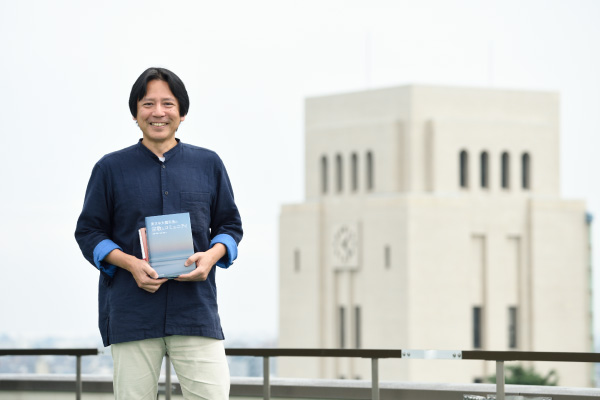

Professor Tatsuya Yumiyama, Religious Studies

Science and engineering students need to

enhance their understanding of religion

Religious studies may sound like an academic discipline providing commentary on Christianity or Buddhism. My classes on religious studies, however, focus on spirituality, or religious awareness independent of any specific religion, and the values held by people.

One purpose for these classes is to enhance the understanding of religion among science students. As explained later, brilliant students in science and engineering surprisingly tend to be drawn into cult religions. The criminals associated with Aum Shinrikyo who perpetrated the subway sarin attack and Matsumoto sarin attack included graduates from the School of Engineering at Tokyo Tech, science faculties of The University of Tokyo, and even a medical doctor who studied at Keio University School of Medicine. The course offered to first-year undergraduate students discusses what faith and belief mean in order to enhance understanding.

Second-year undergraduate students learn via lectures and workshops about the “spiritual boom” and perspectives of life and death held by our youth. For third- and fourth-year undergraduate instruction, we probe into perspectives of life and death held by the Japanese people and ourselves, as we view movies such as Departures, Tokyo Story, and The House of Small Cubes (animation short). In one group-work assignment I ask students to come up with the copy to put on a DVD jacket for The House of Small Cubes. Through the work, students realize that people gain different impressions and interpretations of the same movie.

I sponsor the Seminar on Humanities (Religion and Spirituality in Contemporary Society). Activities include meditation under waterfall at Mt. Takao and exchanges with students from the Faculty of Theology at Sophia University and Faculty of Shinto Studies at Kokugakuin University. Our students, who consider the corporate world to be the norm after finishing graduate school, are actually astonished to find other students of their own age prepared to lead a religious life. The trip to Mt. Takao, initially in a graduation trip mood, takes a turn when other young adults are observed to be quite serious under the waterfall. There are, apparently, others of the same generation who have made choices from options not included in their own list.

One purpose of my religious studies instruction relates to the aim of expanding how students think and see through the surprise and revelation encountered in the activities.

One personal interest concerns the changes in consciousness and behavior of people after the East Japan earthquake. Some people went to disaster areas, volunteered in the aftermath, and continue to live there. The conversations with such people bring forth very religious, truth-seeking, and altruistic words. I am interested in what it means, when people ordinarily dissociated from religion become religious. In the same vein, my interest attaches to the theme of hardship and storytelling, such as the stories of people with illness and the activities of supporters. In recent years, the students and I obtained learning experiences at medical facilities for Minamata disease and Hansen’s disease, and homeless support sites.

Religion is a system of values

Relativization of values liberates the person

The religious studies course for graduate students follows the themes of patriotism and preciousness of life. I pose questions and urge the students to discuss deeply. For example, as an actual situation that occurred at another national university, if the chancellor decided that the national anthem would not be sung at commencement, what would you think? For another, how would you answer the question, why is life so precious?

These themes may cause you to wonder why religious studies consider them. Well, religion is a system of values and meanings, and religious studies inherently contemplate values as an academic discipline. The questions present themes that make you search your own values.

A system of values may not immediately make sense. For example, let us consider the question, “Why is it wrong to kill a person?” People of Christian nations would immediately reply, “That’s obvious, because it says so in the Bible.” People of Buddhist nations would immediately reply, “It’s prohibited in the precepts.” In cultures where a specific religion has foremost currency, many values of society are linked to one religion.

In contrast, asking “Why is it wrong to kill a person?” to modern Japanese who are generally disconnected from religion returns a muffled reply like “Well, it’s against the law.” In 1997, commentators in the TV studio during a news program were stifled by a high school student who actually supplied this answer. This exchange actually became a large story, and many magazines and books were published featuring this program segment. In short, the only explanation is based on the law, because the makeup of one’s own values is vague. Even further, since Japanese society is highly homogeneous, the opportunity to be aware of one’s values is seldom.

That’s why I intentionally push and ask, why do you believe this? Why do you believe it is wrong to kill a person? Further, why do you consider singing the national anthem as a matter of course? Why do you assume that you will go to work at a company after graduation? When an outline of one’s values begins to emerge, relativizing can be accomplished. Then from there, the person can be liberated and enjoy life more, I think.

Truly educated individuals have interests in

other people and the outside world

I came to Tokyo Tech in 2015 and have been involved since the trial teaching phase of Tokyo Tech Visionary Project in relation to the establishment of the Institute for Liberal Arts. My current teaching schedule still includes the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project and Liberal Arts Final Report.

Liberal arts courses sound like a lot of reading and listening to classical music, but there is context to this. The incredibly important aspect is the motivation to read or listen to music, or in other words, being interested in other people and the outside world. The role of liberal arts is to nurture that interest.

With respect to viewing the movies mentioned earlier, it is certainly important to view many movies. Liberal arts, however, can nurture an attitude of taking interest. When the same movie elicits a different impression, such as people coming up with different copy for the DVD after viewing The House of Small Cubes, the aim is to nurture the inquiry, in this case asking, “Why did you come up with that copy?”

In essence, each student is creating an operating system (OS) of human knowledge. If the OS can find interest in a variety of things, the application software like reading or listening to music can be installed later.

I urge Tokyo Tech students to find interest in other people and the outside world. The study of top world-class science and engineering is a given. By gaining interest in differing values and cultures and self-directed learning to deepen humanity, creativity, and sociability, the Tokyo Tech student becomes a versatile force.

The road to attainment is training, I believe. Put the person in environments that encourage interest in various matters, and that person actually may make an effort to take interest. In that sense, Visionary Project and religious studies classes where group discussions take place are great training grounds. Once a week, the opportunity arrives to learn about values different from one’s own and to reflect on why that is the case. This is enough to enhance the emotional “muscle” of young students.

Confined to one’s own values?

Recognize the ability to change

I mentioned at the beginning that science students can be more easily deceived by cult religions.

Cults reach out with a performance of intimacy and their own reasoning. Because many students of science over time have engaged in discourse with numbers and evidence, their resistance to previously unencountered, powerful reasoning and emotional advances appears to be wholly lacking. In addition, cults tend to assess matters as either good or evil, which is familiar to scientific binary thinking.

Tokyo Tech students are no exception, and should realize that they could be more easily ensnared by such values. It is important therefore to be able to relativize one’s own values.

Yet—

Overall, Tokyo Tech students are extremely earnest, conscientious, and able to control themselves. These are high marks that result from the “tough-it-out” experience gained through entrance exam studies.

The self-control and academic excellence, however, lead many to believe they are already accomplished humans. Put another way, the tendency is to steadfastly think that there is no need to change oneself, and that one’s values are not mistaken. These thoughts can be weaknesses.

At the very least, that is definitely a waste. Any amount of change is possible around the age of 20, and more change can broaden and deepen one’s life. Again, life can be liberating and more enjoyable. I intend to continue my support role through instruction of religious studies and liberal arts.

![]()

Professor Tatsuya Yumiyama

Research field: Religious Studies

Born in 1963 in Nara Prefecture. Graduated from Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Letters, Hosei University, and left the Taisho University doctoral program with full credit attained. Previous posts include Research Fellow, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Research Fellow, International Institute for the Study of Religions; Professor, Faculty of Human Studies, Taisho University; Visiting Professor, Eötvös Loránd University. Main research theme in recent years has been the spirituality, and changes in awareness and behavior, in people after the East Japan earthquake. Advisor of a volunteer work group at Tokyo Tech. Author of 天啓のゆくえ―宗教が分派するとき1 (Destination of divine guidance—forming of sects in religion), published by the Japan Institute for Community Affairs, and 東日本大震災後の宗教とコミュニティ1 (Religion and community after the East Japan earthquake), published by Harvest; editor and co-author of many other titles.

Related Works

-

(Religion and community after the East Japan earthquake)

-

(Destination of divine guidance—forming of sects in religion)

-

(Life, education, spirituality)

1 Published in Japanese