Institute for Liberal Arts News

Sharing a Fascination for Novels with Students

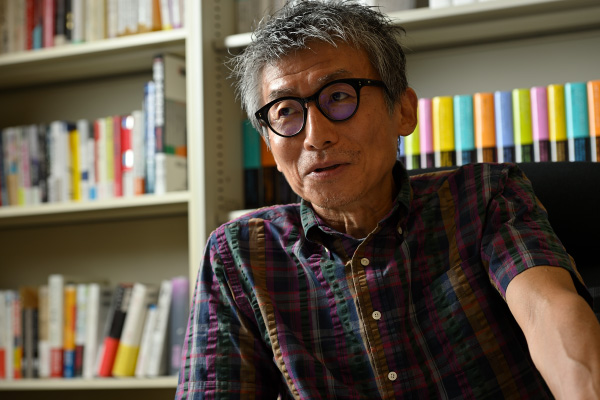

Professor Kenichiro Isozaki, Literature, Fiction Writing

Teaching to find the correct answer

spoils the thrill of reading fiction

I’m teaching literature and fiction writing at Tokyo Tech.

As a literature teacher, my background is somewhat unusual. Having graduated from the Faculty of Commerce at my university, I have no master’s degree in literature. Therefore, my classes may be a bit unique, with more emphasis on thinking about fiction writing from the writer’s perspective than learning academic theories and knowledge. In my Literature A course (for 1st-year undergraduates), for example, every class starts by appreciating works from other art forms, such as music, painting, and video, and then the class analyzes and studies the uniqueness of novels through comparison.

The idea I want to communicate throughout my courses is that there’s no correct answer regarding the intention of the writer.

No music or art exam would ask, “Describe what Mozart wanted to say through this symphony within 20 words,” or “What is Cezanne’s hidden message in this painting?” Strangely, however, this often happens with modern Japanese literature exams at secondary schools. They demand that examinees provide the correct answer. Once, an excerpt from my work was used in a university entrance exam. But honestly speaking, I myself (even the writer) didn’t figure out the correct answer to what I wanted to say by the underlined part in the quiz. More precisely, I didn’t care at all whichever option students took as the answer.

Interestingly enough, many Tokyo Tech students are good at choosing the correct answer (from several options), even in questions I failed. But it’s not because they understand those novels but because they know how to use the elimination method to reach the right choice. I believe that teaching such techniques is the culprit for making today’s Japanese literature class dull.

The expression of fiction only exists in the duration of reading it. The emotions aroused by reading are all that matters, and there are no correct or incorrect answers about feelings.

Let’s take the example of The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka, which starts with the scene where the protagonist wakes up in the morning to find himself turned into a gigantic insect. The scholarly sector admires this work as a monumental masterpiece of absurdist fiction. But, if we read it without any preconception, it may just be read as a series of laugh-prompting comical scenes.

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert is also considered a jewel of French literary realism. While some readers may be baffled by the persistent rendering of the beauty of Emma Bovary throughout the story, I believe that is the best part of reading fiction. Just like we become enthralled by outstanding performances in sports stadiums or zesty rock-music phrases, each sentence in the story can entertain or inspire us. In my classes, I want to share those moments with my students.

Writing fiction and teaching about it

can stimulate the writer in people

I’m a fiction writer myself, but I had no interest in novels in my adolescence; all I did was listen to music. For a rock music boy, however, there were still some works that taught me about the fun of reading, including The Adventures of Kupukupu the Sailor by Morio Kita, which I read in my junior high school days, and One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, which I read when I became an employee. I started that particular novel on my way to work one day, and I couldn’t stop reading, so I had to take a day off—it was so powerfully captivating!

My appetite for novels was unleashed at that point, and I started to read works by various writers. Above all, my encounter with Kazushi Hosaka changed my life. First, I was a fan of his stories, then had the chance to meet him in person, and finally started writing, literally following his recommendation to do so!

I made a debut as a fiction writer at the age of over 40. Since I was still working at a trading company, that was a life of wearing two hats. At first, I was uncertain if I made the right decision, but gradually, while continuing this double-role life, I reached the awareness that I needed to expose my core nature and play by it at critical moments, whether I am working as an employee or writer. Both are the same in the sense that there is no correct answer, and the only thing I can do is always choose what I think is the best. When I realized this, I was confident that I could do both. Thus, my life as a trading company businessperson and an author continued for almost a decade. Then one day, the next awakening came to me.

Contemplating how a powerful “flow” created by Morio Kita, García Márquez, and Kazushi Hosaka had guided me to become who I was, I thought that it might be my turn to pass the baton to the next generation.

If someone that has read my pieces is awakened to the excitement of novels and starts writing themselves, my mission as a fiction creator will be fulfilled. If I can transfer the thrill of written creation to the youth who are bored by modern Japanese classes, I may be able to become a part of a large stream of energy, which has carried me to that point. When I was brooding over such thoughts, I received an offer from Tokyo Tech.

An expected joyful discovery of a new teacher:

Tokyo Tech students have a great chance as a novelist!

It was in October 2015 when I left my company and started teaching at Tokyo Tech. Initially, I belonged to the Department of Value and Decision Science at the Graduate School of Decision Science and Technology, and since 2016, I have belonged to the Institute for Liberal Arts, a newly-founded academy. Since the first year of the Tokyo Tech Visionary Project and Liberal Arts Final Report implementation, I became part of their teaching team. Even though I was puzzled at first with such uncommon methods, I soon came to enjoy life as a teacher preparing for classes. The Visionary Project, for example, is designed to train students to answer questions that have no correct answers. I believe that it can be very stimulating for young men and women who have been taught that learning is all about getting good scores on exams.

By the way, my motto in a Visionary Project exercise is, “We don’t need model answers,” which I announce to 1st-year undergraduates at the beginning of classes. Because many Tokyo Tech students are smart, they know what kind of answers will please teachers.

But I’m not one who is happy with such answers. I always try to be faithful to myself in the class, so I want them to do the same. That is the start of real learning, and it also applies when they choose a topic for their Liberal Arts Final Report. I ask them to choose something they really want to write about since it’s painful to prepare a lengthy report of as many as five thousand words on a topic in which they are not interested. But once their favorite topic is selected, I demand an exhaustive work from them based on thorough research. I even invite them to the library when I think their study is insufficient.

Writing is a solitary activity. Of course, peer-reviewing is necessary during the entire process; however, I also want students to experience the moments of becoming absorbed in their writing, isolated from the world.

As a teacher guiding students through their writing projects, I sometimes encounter rewarding discoveries. For example, in my course named Literature C, which features the one-page-story assignment, every year finds several students who would become finalists in rookie awards if they were to write a novella. You can trust me on this because I serve as a judge in literary competitions outside the campus. For science students, their odds for writing success are pretty high. In fact, there are many novelists with a scientific background. Morio Kita and Junichi Watanabe were medical doctors, while Natsuki Ikezawa and Hiromi Kawakami once studied physics and biology, respectively. As for Tokyo Tech graduates, there is Takaaki Yoshimoto. It’s my speculation that scientists, often free from stereotyped respect for literature, may be more open to the new and unimaginable.

Foster and continue polishing a uniqueness that is unbeatable

I have the impression that many Tokyo Tech students are the masters of one art. In other words, they pursue things related to their specialized fields as thoroughly as they can and show little interest in other activities. I find no argument in that. You may think that liberal arts education aims to round out sharp-edged differences among things you are good at (or like) and those that you are not good at (or do not like). However, there may be another perspective: further sharpen what’s already sharp. Of course, it’s not about being narrow-minded, but a new, broader view may be open when standing at the peak of steepness.

So, please keep fostering your unbeatable strength in your strong field. Tokyo Tech is a learning place where you can make it razor-sharp. I hope you can pinpoint your effort on what you want to do and reach its core. By doing so, you can master the skills to liberate yourself from various restraints, which, I believe, is one of the aims of learning liberal arts.

![]()

Professor Kenichiro Isozaki

Research Fields: Literature, Fiction Writing

Born in Chiba Prefecture in 1965. Graduated from the Faculty of Commerce, Waseda University in 1988 and joined Mitsui & Co., Ltd. Began writing novels shortly before the age 40, recommended by Kazushi Hosaka, a writer. Received the Bungei Prize for Children of Essence (Kawade Shobo Shinsha), making a debut as a writer in 2007. Other prizes include the Akutagawa Prize for Last House (Shinchosha) in 2009, the Tokyu Bunkamura Deux Magots Literary Prize for A Pair of Total Strangers Very Much Alike (Kodansha) in 2011, and the Izumi Kyoka Award for Past That’s Gone, Future to Come (Bungei Shunjusha) in 2013. Left Mitsui & Co., Ltd., where he worked for 27 years in September 2015. Became a professor at the Department of Value and Decision Science, Graduate School of Decision Science and Technology, Tokyo Institute of Technology in October 2015. The current position since April 2016. Other works include Eye and Sun, Discovery of the Century (both Kawade Shobo Shinsha), Train Road (Shinchosha), Animal Caricatures (Kodansha), Kintaro Candies: Collection of Essays, Interviews, and Reviews by Kenichiro Isozaki 2007- 2019 (Kawade Shobo Shinsha), etc. Note: Book titles are translated.

Related Works

-

Children of Essence/Eye and Sun

-

終の住処1

Last House

-

金太郎飴 磯﨑憲一郎 エッセイ・対談・評論 2007—20191

Kintaro Candies: Collection of Essays, Interviews, and Reviews by Kenichiro Isozaki 2007- 2019

1 Published in Japanese