Institute for Liberal Arts News

Learning the Values of Coincidence Through Art and Becoming Free from Your Need to Control

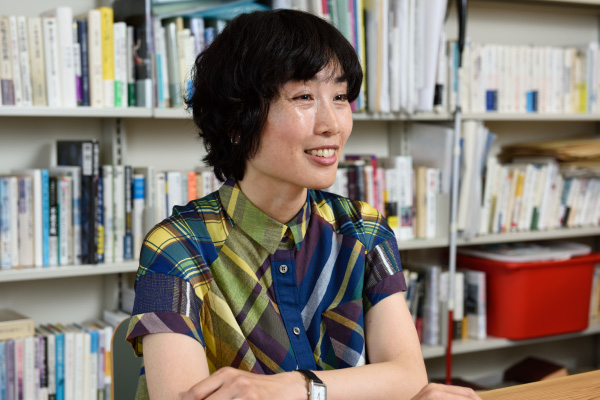

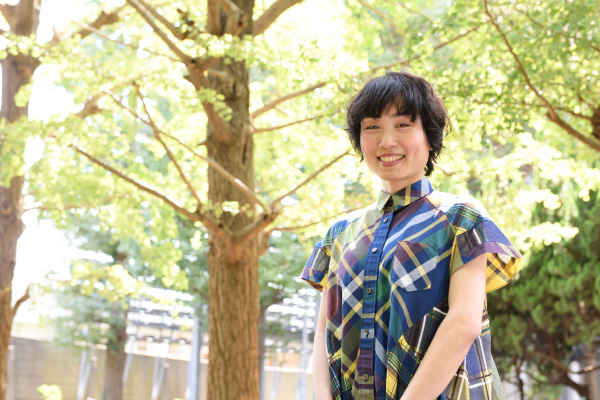

Associate Professor Asa Ito, Aesthetics, Contemporary Art History

Tokyo Tech students hate Jackson Pollock’s abstract paintings

I’m in charge of aesthetic art courses.

As the only teacher of painting and sculpture at Tokyo Tech, my courses include sessions for art appreciation, production, and learning histories. The art history course for 1st-year undergraduate students covers topics from the Parthenon to 19th-century art, while for the 2nd-year course, you will learn about events since the 20th century. However, as my specialty is aesthetics, not art history, I will focus on human perceptions of beauty, the background behind the creation of specific art pieces, and how scientific advances have influenced people’s sense of beauty.

Liberal arts are sometimes defined as “the arts for liberating yourself,” and that is where I intend to help you so that you get freedom—at least to some extent—from your fixed ideas. To do that, I will show you a new perspective that’s different from the one you probably used to have.

That perspective refers to the “values of coincidence.” Arts value elements of coincidence. Put differently, unpredictably made pieces are more thrilling than those produced as planned. My impression of Tokyo Tech students says that they are not good at appreciating such values. For example, my classes use slides of various artworks, which I show them without a detailed explanation, and then I ask them what they feel.

Then, some types of art are disliked by Tokyo Tech students, even though the works are popular among the general public. One such example includes paintings by Jackson Pollock, a major abstract impressionist from the 1940s to 1950s.

Pollock’s method is called “dripping,” which features splattering paints directly on the canvas instead of preparing a sketch drawing. To some students at Tokyo Tech, his works even cause disgust. However, I believe feeling disgust can be the turning point of changing one’s perspectives. When I ask them why they hate paintings using dripping, many of them would answer, “Because there’s no reproducibility in this picture. It’s just the result of coincidence.”

For science students, repeatability is crucial in the sense that anyone should be able to achieve the same result. That’s the name of the game for scientific theories, and control is one of the top needs for any engineer. In that sense, Pollock’s works are not controllable (at least, that’s how they seem), and that may be what provokes their detest.

But there lies the chance of new learning for Tokyo Tech’s science students. Control is not everything in the real world. On the contrary, there are many unmanageable things, such as disasters or large-scale accidents. The world of reality holds a zone beyond human or even machine control. I believe that art expressions can awaken you to that, and guiding you to there is my mission as an art teacher at the university.

Exploit a 90-minute class to learn a new perspective

While verbally re-rendering “disgusting” art pieces, the viewer’s way of feeling may change. One student said that they could enjoy Pollock’s paintings in the same way they enjoy soccer games. According to him, there are two forms of entertainment. The first is the repeatable one, such as scripted theater, which is intriguing. Another is the one-time-only type such as an exciting sports performance. Then, Pollock’s paint drips on the canvas can be compared to the traces of physical movements, and seeing them is like reviewing the soccer game via broadcasting.

He compared the painter’s artworks as a representation of dynamism or live sensation, which was quite impressive. As a teacher, it’s thrilling and rewarding to see how students learn a new perspective and start to see things differently in just 90 minutes!

Then, what kind of art do Tokyo Tech students love? It’s conceptual art or something featuring mathematical elements. Specifically, a work by Yoko Ono, which says, “This line is a part of a very large circle,” is their favorite.

In the 3rd-year classes, students will create their works. The 2018 course included the theme “Implement Doraemon’s Secret Gadgets.” The concept behind the project is a challenge to a usual engineering perspective of building practical and useful things. I wanted them to experience creating something purely conceptual instead of that.

For a more focused creation experience, there is my small-group, five-day intensive seminar. Each class gives you a different assignment, and you will create something based on the theme. For example, I would give each of you a tissue paper box and the subject: “Deny the tissue paper box.” The term “deny” here means to turn the item (here, a tissue paper box) into something most distant from that.

Creating artworks is essentially denying something on which art is performed. Painting, for example, is based on the denial of a sheet of cloth called a canvas. Sculpture “denies” the wood or stone to turn it into something else.

By the way, it’s fantastic to see how a thing can turn into something previously unimaginable. For example, when I assigned the subject “Deny Duct Tape,” one student made “Kakuni,” a Japanese braised pork dish, out of it. Japanese brown duct tape, cut radially, does look like braised pork.

Besides working on activities to turn things into something else, students will go through a session to write fiction (I know it’s quite a tough course for them!).

Creating something every day will deplete your ideas and empty your mind, revealing the essence of what you are. In that sense, this five-day intensive course gives you the time to face yourself.

As an extra-curricular activity, I also supervise study sessions where we read philosophy books. The activity was prompted by a student learning fluid mechanics, who turned to me for advice on philosophical literature related to flows. At first, it was a one-on-one session with the student for reading Bergson and Erich Fromm. Then it rapidly expanded to include such a large membership that I had to ask for help from teachers such as Takeshi Nakajima and Yoshimi Takuwa in overseeing the activity.

Currently, each session follows an established process, where the organizer (a student) produces a summary sheet used in the activity. Attending those sessions often reminds me of the essence of a liberal arts education. Tokyo Tech students have a scrutinizing mindset trying to get to the bottom of what they pursue, and for that, they look somewhat dignified. Some students even create an incredibly excellent summary. Seeing all this is indeed a wonderful and rewarding privilege as a teacher.

“How do they feel in their bodies?”

—The starting point of my research

Another research theme, in addition to art, is the body as an organism. My initial plan in the first and second undergraduate years was to become a biologist, and it was based on the idea that I wanted to experience living in a non-human body. Thinking about how life in a brainless insect form, for example, can make decisions or what’s happening within other corporeal forms intrigued and thrilled me. Though I didn’t become a biologist, that interest brought me to the current study of how differently the bodies of other people (conditioned differently from mine) would work. Particularly, my research focuses on physically disabled bodies.

I said that art had values of coincidence in the previous section, but the organic body that one is born into may be the ultimate combination of coincidental factors. You came into existence in a biological container of a specific race, gender, face, shape, and constitution—through various incidental factors. You couldn’t choose, you have been just given that body, and life is a process to embrace those coincidences as inevitable. Your body is a mass of incidental outcome and the prerequisite that’s always governing you. I think that how to deal with this default condition is an essential question of life.

The results of my research and study will be available not only in papers but also in books. My latest book, Kioku suru karada (The Remembering Body), spotlights acquired disabilities or disabilities developed at some point in life. Compared with congenital cases, acquired disability cases can be complicated since the holder of that body still has memories of non-disabled functions. In a body with acquired disabilities, something has changed, but there are things not affected by the disabilities. The body contains a part of the person who once was healthy and another part, who is now disabled. Living in such a two-in-one state inevitably produces a physical sensation of a gap, and those gaps are described in the book. It’s impossible to leave this coincidental body we have, but still, it may be possible in our imagination. Thus, the question “How do you feel in your body?” always motivates my further study.

Liberal arts seeds continuously planted since 2013

now start to bloom

I joined the Center for Liberal Arts, the predecessor of the Institute for Liberal Arts, in 2013. Together with professors Akira Ikegami, Toshio Kuwako, and Noriyuki Ueda, I was one of the original members. In Japan in those days, the term “liberal arts” itself was seldom heard. As far as I remember, it was the case not only in Tokyo Tech, but also in society at large.

Therefore, it was notable that our center announced the importance of liberal arts education. Our emphasis lied in education as the means to foster human qualities instead of simply transferring art-related knowledge. We used to refer to this as “Education to enhance the roots,” analogizing people to trees.

It was an unprecedented challenge, so I started learning about liberal arts education to its core. Within two years, I visited various schools in and out of Japan to observe how they practice full-fledged liberal arts education. The list of visits includes Oxford, Cambridge, and Imperial College in the U.K., and Caltech and UC Berkeley in the U.S. My mind was filled with the question, “What should we do to provide excellent liberal arts education?” and my thoughts were reported and shared with other members every day. In retrospect, those were days of spreading the seeds of liberal arts and then carefully nourishing them—such luxurious moments of life as a teacher!

The center developed into a new organization (the Institute for Liberal Arts) in 2016, and the teacher population increased by several tens of times. It’s utterly surprising to see how the seeds that were constantly planted and carefully nurtured have developed into such a large flower garden. It’s still something incredible even now.

Since the curriculum of the Institute for Liberal Arts started, even students seem to have changed. When I joined the center, the font size of their comment sheets was so small—say, size five—but now, it’s as large as size eleven. Back then, they were probably not confident about their comments, since they thought teachers would not be interested in what they were saying. Currently, small-member classes, on the other hand, can trust that their voices are surely heard. Interestingly, the size of letters may reflect the writer’s confidence and will to communicate.

Some say that liberal arts education is not readily useful, but I don’t think so. What’s the purpose of learning to begin with? To enhance academic activities? Of course, some fields are not practically applicable to our life. However, in most cases, learning aims to solve issues in the real world. Social needs should always come first, not academic knowledge. But addressing the problems in the real world requires learning related to various cultures, lifestyles, and beliefs. Empathy for others is also essential. I believe that the answers to the question of how to locate, define, approach, and solve social issues often may lie in a liberal arts education.

![]()

Associate Professor Asa Ito

Research Fields: Aesthetics, Contemporary Art History

Enrolled at the Natural Sciences II of the University of Tokyo and started to study biology in 2001. Changed to Aesthetics course in 2004. Completed the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology at the University of Tokyo and received a Ph.D. in Literature in 2010. Joined the Center for Liberal Arts, Tokyo Institute of Technology as an associate professor in 2013 after completing the JSPS Research Fellowship. The current position since April 2016. Worked as a visiting researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from March to August 2019. Authored books include ヴァレリーの芸術哲学、あるいは身体の解剖1 (Valéry’s Philosophy of Art or Anatomy of the Body), 目の見えない人は世界をどう見ているのか1 (How Do People Without Sight See the World?), 目の見えないアスリートの身体論1 (Theory on Blind Athlete’s Body), どもる体1 (The Stuttering Body), and 記憶する体1 (The Remembering Body).

Related Works

-

(How Do People Without Sight See the World?)

-

どもる体1

(The Stuttering Body)

-

(The Remembering Body)

1 Published in Japanese