Life Science and Technology News

A pheromone-sensing gene that predates land-dwelling vertebrates

Scientists at Tokyo Tech have discovered a gene that appears to play a vital role in pheromone sensing. The gene is conserved across fish and mammals and over 400 million years of vertebrate evolution, indicating that the pheromone sensing system is much more ancient than previously believed. This discovery opens new avenues of research into the origin, evolution, and function of pheromone signaling.

(A)

(B)

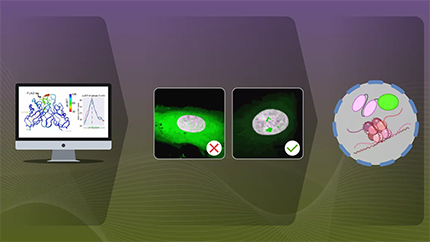

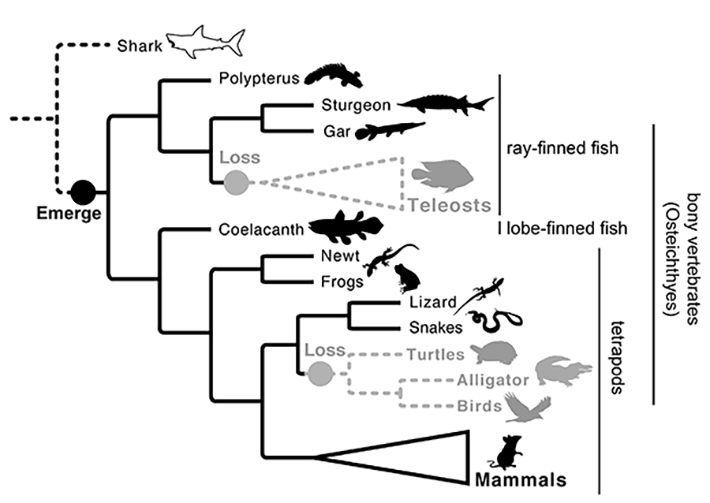

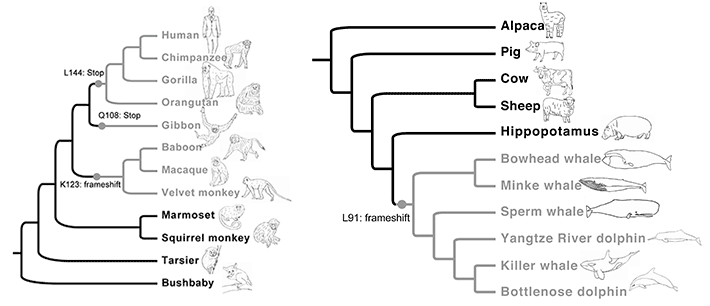

Figure 1. Single emergence and two major losses of ancV1R gene during vertebrate evolution.

(A) ancV1R emerged in the common ancestor of bony vertebrates (black circle) and was lost in each of the common ancestors (gray circles) of teleost fish and of turtles, alligators, and birds (gray dashed lines and silhouettes). White silhouette and dashed black lines associated with shark indicate that ancV1R has not yet emerged.

(B) Examples of ancV1R loss events in higher primates (left) and cetaceans (right). The gray branches indicate the lineages in which ancV1R has been lost and the vomeronasal organ is absent. The timing of the mutations causing loss of ancV1R is shown above or below the gray circles.

Associate Prof. Masato Nikaido at the laboratory

Most land-dwelling vertebrates have both an olfactory organ that detects odors and a vomeronasal organ that detects pheromones, which elicit social and sexual behaviors. It has traditionally been believed that the vomeronasal organ evolved when vertebrates transitioned from living in water to living on land. New research by Masato Nikaido and colleagues at Tokyo Tech, however, suggests that this organ may be much older than previously believed.

The vomeronasal organ contains receptors in the V1R protein family that are crucial for pheromone detection. Nikaido et al. identified a gene, ancV1R, that encodes a previously unknown member of the V1R family. However, unlike other V1R genes, ancV1R is present not only in land-dwelling vertebrates but also in some fish lineages, indicating that it has been conserved over 400 million years of vertebrate evolution. According to Nikaido, this finding was “quite surprising, as this represents the first discovery of a V1R family gene shared between fish and mammals.”

The authors identified ancV1R in 56 of 115 vertebrate genomes. Interestingly, the loss of ancV1R in some vertebrate lineages, such as higher primates (including humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas), cetaceans (including whales and dolphins), birds, and crocodiles, corresponds with the loss of the vomeronasal organ in these lineages (Fig. 1). The findings suggest not only that ancV1R may be a vital component of the vomeronasal organ, but also that this organ predates the transition of vertebrates to land, opening a new avenue of research into its origin.

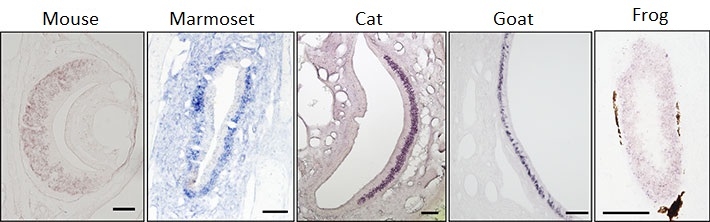

Figure 2. ancV1R expression in diverse vertebrates

Examined frozen sections of the vomeronasal organ in diverse vertebrate by in situ hybridization, a signal indicating the gene expression of ancV1R was obtained.

ancV1R is also unusual in that it is expressed in most vomeronasal sensory neurons. In contrast, other V1R proteins follow a “one neuron–one receptor” rule, with only a single receptor being expressed in each neuron. This further demonstrates the importance of ancV1R in pheromone sensing. As noted by Nikaido, “It will be fascinating to further investigate how these patterns of expression are regulated and to determine their functional role in chemosensory signaling.”

Reference

| Authors : | Hikoyu Suzuki1,2, Hidefumi Nishida1, Hiro Kondo1, Ryota Yoda1, Tetsuo Iwata3, Kanako Nakayama1, Takayuki Enomoto1, Jiaqi Wu1, Keiko Moriya-Ito4, Masao Miyazaki5, Yoshihiro Wakabayashi6, Takushi Kishida7, Masataka Okabe8, Yutaka Suzuki9, Takehiko Ito1, Junji Hirota1,3, Masato Nikaido1 |

|---|---|

| Title of original paper : | A single pheromone receptor gene conserved across 400 million years of vertebrate evolution |

| Journal : | Molecular Biology and Evolution |

| DOI : | 10.1093/molbev/msy186 |

| Affiliations : |

1 School of Life Science and Technology, Tokyo Institute of Technology 2 Nihon BioData Corporation 3 Center for Biological Resources and Informatics, Tokyo Institute of Technology 4 Department of Brain Development and Neural Regeneration, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science 5 Department of Biological Chemistry and Food Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture, Iwate University 6 Institute of Livestock and Grassland Science, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) 7 Wildlife Research Center, Kyoto University 8 Department of Anatomy, The Jikei University of Medicine 9 Department of Medical Genome Sciences, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo |

- Labs spotlight #14 - Nikaido Laboratory

- Nikaido Laboratory (Japanese)

- Researcher Profile | Tokyo Tech STAR Search - Masato Nikaido

- Department of Life Science and Technology, School of Life Science and Technology

- Latest Research News

School of Life Science and Technology

—Unravel the Complex and Diverse Phenomena of Life—

Information on School of Life Science and Technology inaugurated in April 2016

Further Information

Associate Professor Masato Nikaido

School of Life Science and Technology,

Tokyo Institute of Technology

Email mnikaido@bio.titech.ac.jp

Tel +81-3-5734-2659